Executive Director of Fundraising

Many years back, I was talking to a friend of mine who had just taken over as the executive director for a medium-sized non-profit. This friend was highly trained for the kind of social work this organization did, but I distinctly remember hearing a deep sadness in his voice while we discussed his new role over a beer.

“I just didn’t think I’d have to be doing so much fundraising. I feel like that’s my entire job now.” he remarked.

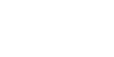

And while I’ve spent my whole career in the for-profit world, I definitely know this feeling. It’s the feeling of missed expectations – the kind of frustration that arises when you finally land what you think is your dream job, balancing passion and profession perfectly, only to discover that the minute you stop spinning these plates you never knew existed, your whole job will unravel. I know this feeling because it’s the same tension I experience when being pulled between selling and executing for Pathos Ethos.

No that’s not really us. But it is how we feel.

The fascinating thing for my friend’s situation, however, did include a nuance that I’ve never had to experience before, and it stems from a subtext behind my friend’s melancholy; the B-plot to his micro career story arc. It’s the deep sadness of someone who was dropped into a leadership role because of their subject-matter expertise, but unprepared to succeed because management is an expertise unto itself.

“Our company is worth nothing. That’s the difference between you and I.” – Michael Scott

Additionally, my friend felt unprepared not just because he had no experience fundraising, but also because, for the first time in his career, he now had to deal with proving himself to people who didn’t work with him daily, the same people that had hired him: his non-profit’s board of directors.

At the time, I thought, “wow, that’s fascinating to hear that you got bait-and-switched by your well-meaning non-profit job.” A few years after that, my thinking had changed into, “I guess, that’s just what all ED’s do.” And only now, after having worked with so many non-profit clients, do I realize that non-profit business models are extremely complex, typically more so than similar-sized for-profits – if only because of the multi-layered value exchanges almost all non-profits have to balance (donors, clients, board members, staff). In other words, both my previous reactions to my friend were painfully reductionist and probably harmful.

Since then, I’ve come to realize that while no magic bullet exists, in the case of two of these value streams, the donor base and the board of directors, both parties actually need the same thing from their executive director: showing their organization’s impact. And impact, is the magic word that unlocks all kinds of doors.

Both the donor base and the board of directors need the same thing from their executive director: showing their organization’s impact.

At the end of the day, both fundraising and board accountability come down to convincing stakeholders that their participation and investment are making a difference through you and your team.

Social Good Metrics

So, sure, showing impact is great, but most would agree that is easier said than done. For example, how do you do it for non-profits when impact might be something largely intangible? We pondered these questions for years and while the answer inevitably always came back to some form of metric science, I kept getting pushback from my clients in primarily two forms:

- I don’t want to summarize my social good with a number. Metrics dehumanize my organization’s social impact. If I have them, it means that’s all my board will pay attention to.

- Even if I wanted to, I wouldn’t know how to visualize my social impact. It’s impossible to measure the kind of non-profit impact my organization makes. I don’t even know where to start!

While both of these hesitations are absolutely valid reasons to be wary of hastily crafting sweeping business strategies on the first metric you decide to start paying attention to, both can be addressed through – you guessed it – even more metrics.

Not All Metrics Are Equal

On the first point: For you veterans of social impact work, we’ve seen time and again that there is a very real fear of misrepresenting your social impact through some abstract number. After doing a number of strategic consulting gigs, however, we’ve found that that specific fear can be addressed by actually embracing metric science more fully rather than backing away from it.

Here’s an example. Say you have an ugly puppy-saving non-profit and last month your team was able to get 25 ugly puppies adopted. Your board and your donors, however, are comparing you to the national Red-Rover-Cross down the street and are asking for you to improve your overall puppy adoption rate. Sound familiar?

Comic Sans anyone?

No, I definitely did not spend four hours on this logo.

Here’s where we’ve discovered better impact metrics can help. While you might be tempted to acquiesce to your board’s demands and go for the easy wins just to get your overall puppy adoption numbers up, what you could do instead, is better define the qualities of success. Define your success metric by saying that you only save ugly puppies because those are the ones that actually need your help; and saving 25 at-risk puppies every month is much greater social impact than saving 100 puppies who would have gotten adopted anyway without your help.

Saving At-Risk Puppy = 250 Social Impact Pts, x25 Ugly Puppies = 6,250 Social Impact Pts

Saving Cute Puppy = 12 Social Impact Pts, x100 Cute Puppies = 1,200 Social Impact Pts

In other words, picking great qualifying metrics for your successes ends up forcing you to pay attention to the quality of impact you’re hoping to achieve, rather than just the quantity of a diluted one.

So How Do I Even Start Visualizing Impact?

The second pushback we see often to metrics comes out of not even knowing where to start. This is probably the more common pushback between the two we see, and it’s definitely because the root issue of unmeasurable impact is made infinitely more complicated if the non-profit you’ve established has lofty impact goals/visions/dreams. For example, how do I visualize solving world hunger? How do I measure social change as a result of my racial equity education programs? As much as I want it to be true, there’s no such thing as a Social Impact point system.

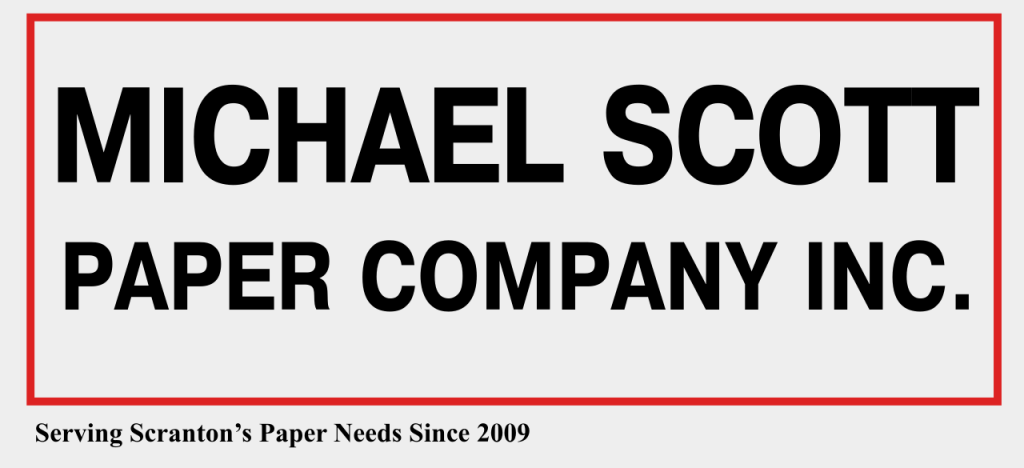

So to better answer these types of questions, we turned to a metric framework that we lovingly call the “POOI framework” here in the office. While we’ve heavily adopted it for our own purposes, it originates from Robert Penna’s outcomes measurement. Here’s our take on it:

All quantifiable non-profit metrics (and for that matter for-profit metrics) will fall on the following spectrum, roughly categorized into four buckets:

- Process: The measurements of all the things that your organization does to keep doing what it’s doing. In our ugly-puppy saving non-profit example, this would include things like:

- How many at risk ugly-puppies did we identify and put into our system?

- How many people have joined our lists to be notified when a new adorable ugly-puppy is rescued

- Output: The quantity of direct yield by your organization’s activities.

- How many puppies did you find new homes for?

- Outcomes: The measurement of observed effects that result directly from your output.

- How many happy homes did you create through your adoption?

- How many puppies did you make extremely happy through your adoptions?

- Impact: The total sum positive improvement your organization hopes to achieve.

- What percentage of dog owners did you convert to ugly-puppy lovers?

- How much improvement did you measure in total dog rescues in the world?

As you can see, even within this tongue-in-cheek example of saving ugly puppies, there’s tremendous difficulty and ambiguity in just categorizing or naming what those metrics are supposed to even be. Don’t panic, however, if you can’t immediately figure out how these metric buckets should be defined for you. Like all tools, use this framework in a way that’s helpful for you. At the very least, it can help you define some rough categories around what you’re trying to look for so that when you get there, you’ll recognize it immediately in context.

Stories Are Tactical, Not Strategic

Once you’ve at least thrown a few ideas up on the POOI board for your impact metrics, the next helpful thing is to understand that measurements correlate to cost. Let’s say your non-profit is a national organization that seeks to solve world hunger. Your impact goals might include something like measuring how hungry every human being on earth is. While the impact goal itself might seem obviously easy to identify, actually gathering that measurement is most certainly going to be cost prohibitive. Here’s a picture that helps describe this impact metric cost relationship:

The further towards impact your measurement gets, the more it’s actually going to cost your organization to measure (even after overcoming the hurdle of just identifying them). In our most recent example, you’d find that there are entire organizations devoted to just measuring world hunger, let alone trying to solve that problem. Having your organization take on measuring that impact metric while also trying to make that needle move, might bankrupt your organization before you even get to share a meal with hungry people.

Thankfully, we’ve discovered a few ways to help make measuring impact more achievable. Here are two ways that we’ve figured out can help:

- Decrease scope: It’s a lot easier to measure hunger in Durham, NC than it is the entire world. Then you can sample.

- Decrease frequency: The U.S. Census Bureau only measures the U.S. population once every ten years for a reason.

Taken to the furthest extreme, this is exactly what a good success story for your non-profit is. One success case (limited frequency) that had a specific desirable outcome (one scope). As an ED or a marketing director for your non-profit, this is extremely helpful because once you understand story as a singular example of an impact metric, you’ll understand that a success story is really a tactical impact metric, not a strategic one.

A success story is really a tactical impact metric, not a strategic one.

While these are important and at least leave you with something rather than nothing, you can’t build a system that shows impact repeatedly and purposefully if you don’t understand it in the larger picture of how you’re showing the impact you’re achieving.

The Goal(s)

Now chances are you and your organization probably have a large percentage of these metric pieces already in place, you’ve just never put these together in a single visualized framework.

And in the event that you don’t have some solid impact metrics to show your stakeholders or donors, let me reiterate, great impact metrics are valuable and extremely helpful, but it’s not the end of your organization. According to a study done over at Harvard Business School, it’s actually better to be strategic about where along the POOI spectrum you’re going to be measuring most.

In conclusion, if you don’t know where your organization is in its own health, or you don’t know how to prove to your board or donors that your non-profit is having impact, here’s what you can do:

- Identify your quality metrics (not just quantity ones)

- Try to push your metrics to the right of the POOI spectrum as much as possible without breaking the bank

And yes, like always, while we know that all of this is easier said than done, if you don’t know how to get to the next step, or you don’t even have time because you’re spinning so many other plates, feel free to schedule a quick chat, we’re happy to help.